Originally posted March 27, 2024

Mark Rothko was found dead on the floor of his studio on February 25, 1970. What ensued from his death was the largest lawsuit ever to take place in the art world. Brought by Rothko's children, Mell and Christopher Rothko, the suit resulted in a 9 million dollar award against the Marlboro Gallery, the executors of his will were thrown out, and severe restrictions were placed on co-conspirators, agents, and fellow artists who were found to have been complicit in the fraudulent acquisitions.

Now, with the help of Rothko's children, the Vuitton Foundation has assembled one of the largest collections of Rothko's work ever exhibited, including many of his early works, as well as the "classic" works of the late 1950s and later "black" paintings of the 1960s.

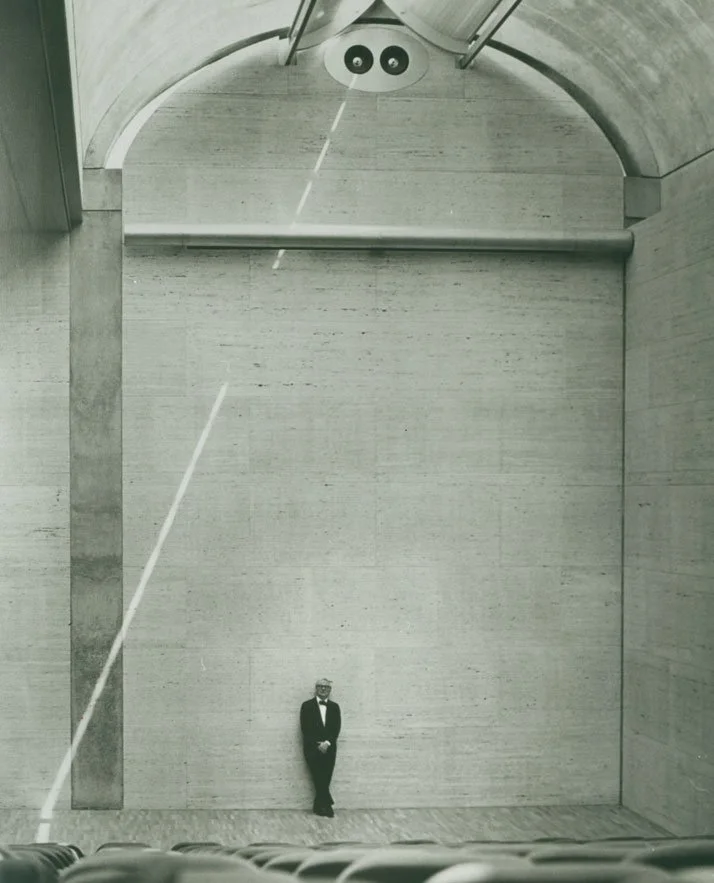

Housed within a titanium butterfly designed by Frank Gehry, The Vuitton Foundation lies within the Bois de Boulogne, removed from the settings in which one normally sees Rothko. The magnitude of this exhibition and the care with which it has been hung makes for an overwhelming experience. The exhibition is not likely to travel as complete or intact, as only the Vuitton's resources have made it possible, and this adds to the sense that this is a once in a generation event.

Standing before a Rothko painting is to stand before an apparition. The paintings are large, in statuary terms, one and a half times life-size, so that you are surrounded. Hung near the floor, per Rothko’s protocol, you are a step away from being in them.

The paintings appear to have light emanating from within. These paintings cannot be successfully photographed or reproduced. Even the most expensive catalog or monograph produces cadaverous images by comparison to the real thing. This effect was not easily arrived at overnight, and one of the fascinating aspects of the exhibition was to see Rothko's evolution as a painter until he reached a chromatic peak in the early 1950s.

Rothko always rejected the term color-field painter, applied to him by the eminent critic, Clement Greenberg. He claimed not to be interested in color, but rather in light, and while this might sound dissembling, it is entirely accurate when you stand in front of one. The process began with raw canvas, stained in the palest of pigments, with successive layers of color applied, at first in more analogous and pale pigments, and later in more complementary, even lurid colors. With generous amounts of turpentine, each block appears as a kind of translucent cloud. Your mind insists on a virtual space behind the canvas, and this is reinforced subliminally as the color is held back from the edge of the canvas. The background, the original stained surface, is often modified with a pale coat of Zinc White, to create a kind of apparent perspective behind the color blocks, whose “sfumato” edges remain indeterminate.

The allusion of these paintings is aspirational or nuclear, depending upon your point of view. Rothko talked about raising the emotional level of painting to that of music, and it could be said that these paintings in the late 1950s were composed in a major key. Soon he began to compose in a minor key, at first deepening the register of his color palette to dark blues, maroons, and purples, sometimes with the introduction of black, and eventually in the late 1960s, to entirely black.

The phenomenon that emerges from the black paintings is one, paradoxically, of complete color. It is as if your mind refuses to accept that color is not there. You become, as Emily Dickinson said, "…accustomed to the dark." The condition exists entirely in your mind. It is why these works are, as Rothko said, not paintings, but experiences.

Toward the end of the exhibition, in one of the last galleries, sits Painting No. 8 (1964), one of the largest paintings in the exhibition. It is approximately seven feet wide by nine feet tall. Across the room, it exudes a soft, reflective glow, but as you approach, it becomes more immeasurable and unattainable. You turn your head to scan its vast and unknowable surface. I went back to view this painting several times, to fathom it, and did not succeed. On my last visit, I heard a cry coming from near the painting and soon realized it was a young woman. The guards came to console her. “How can you look at this painting and not weep,” she said.

No. 8 (1964) National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.