Franz Kline

Franz Kline's Black, White, and Gray (1959) is nearly nine feet tall and nearly seven feet wide. I came across it in person at the Met a few months ago. It’s overwhelming.

It's also a departure from the minimalism of his earlier black and white paintings, and while leaving aside the doctrinal definitions of minimalism, a couple of things are apparent in works that fall under this definition. One is the lack of reference or narrative, such that the experience of the artwork is entirely subjective. Think of the Donald Judd aluminum cubes or a Rothko painting. They are not about anything else. They are only about themselves, and as such, they are understood directly, or not, depending on your disposition.

Another characteristic is that they remain open, in that you can never quite get your head completely around them. They resist interpretation. There is a lack of middle ground, and that is particularly true in the earlier works of Franz Kline. They are black and white, black in the foreground, white in the infinite, beyond. They are not located in space, but rather imprinted in your mind, much as a Rorschach test. Close your eyes, and they are still there.

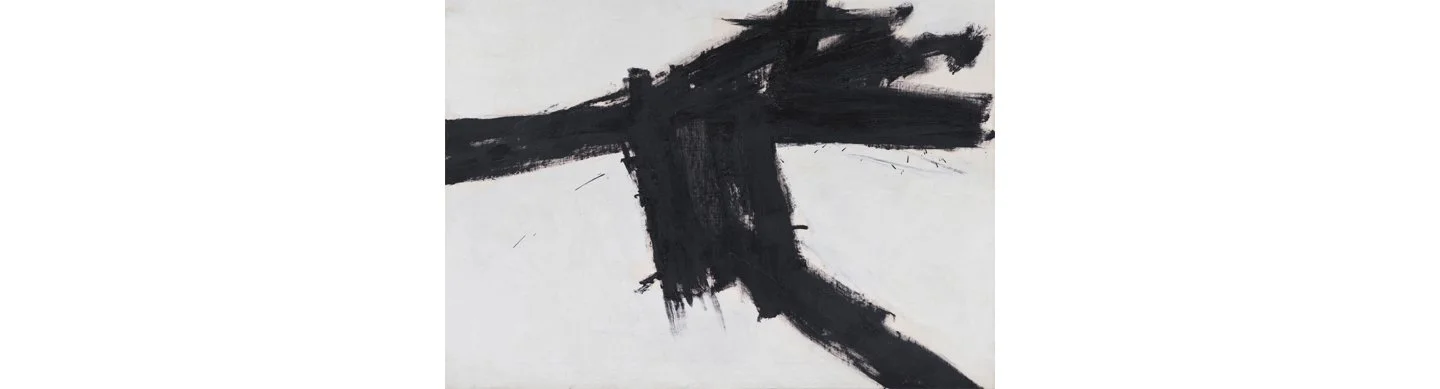

Buttress (1952)

Kline famously got his start when William DeKooning introduced him to a Bell Opticon projector. With it, he found that he could take small sketches and enlarge them onto a wall, where, as fragmentary images, they became less recognizable and more monumental. Many of these came from sketches drawn on pages of old phone books. In the beginning, these small drawings might be of a chair which, when projected, gave the negative space, say between its slats, just as much presence as the slats themselves. He once famously said that he painted the white just as much as he painted the black.

Intersection (1955)

It was the boundary between the black and white that became more ambiguous over time, where Kline discovered another emotional dimension. It was as if once again, he had taken the Bell Opticon to enlarge an unstable boundary to the point of nuclear fission.

In another departure, he introduced not simply black and white, but Ivory Black along with Mars Black, Flake White along with Zinc White, one cool and one warm in each case, and in addition, when certain whites were introduced to certain blacks (e.g., Zinc White to Ivory Black), blues were suddently implied.

Black, White and Gray (1959) Detail

And this is not just a visual phenomenon, but much more. It puts you in a liminal space. Every stroke, every shade is in the process of becoming. You are aware of time, what came before, what will come afterward, and while this painting has been described as an "action" painting (vis. Pollock), most of the action is taking place in your evolving awareness.

If all of this seems overwrought, I encourage you to go and take a look for yourself sometime, next time you're in New York. It's at the Met, on the third floor, in Gallery 919, along with some other extraordinary works of the mid-20th Century.

Hardly anyone is ever there.